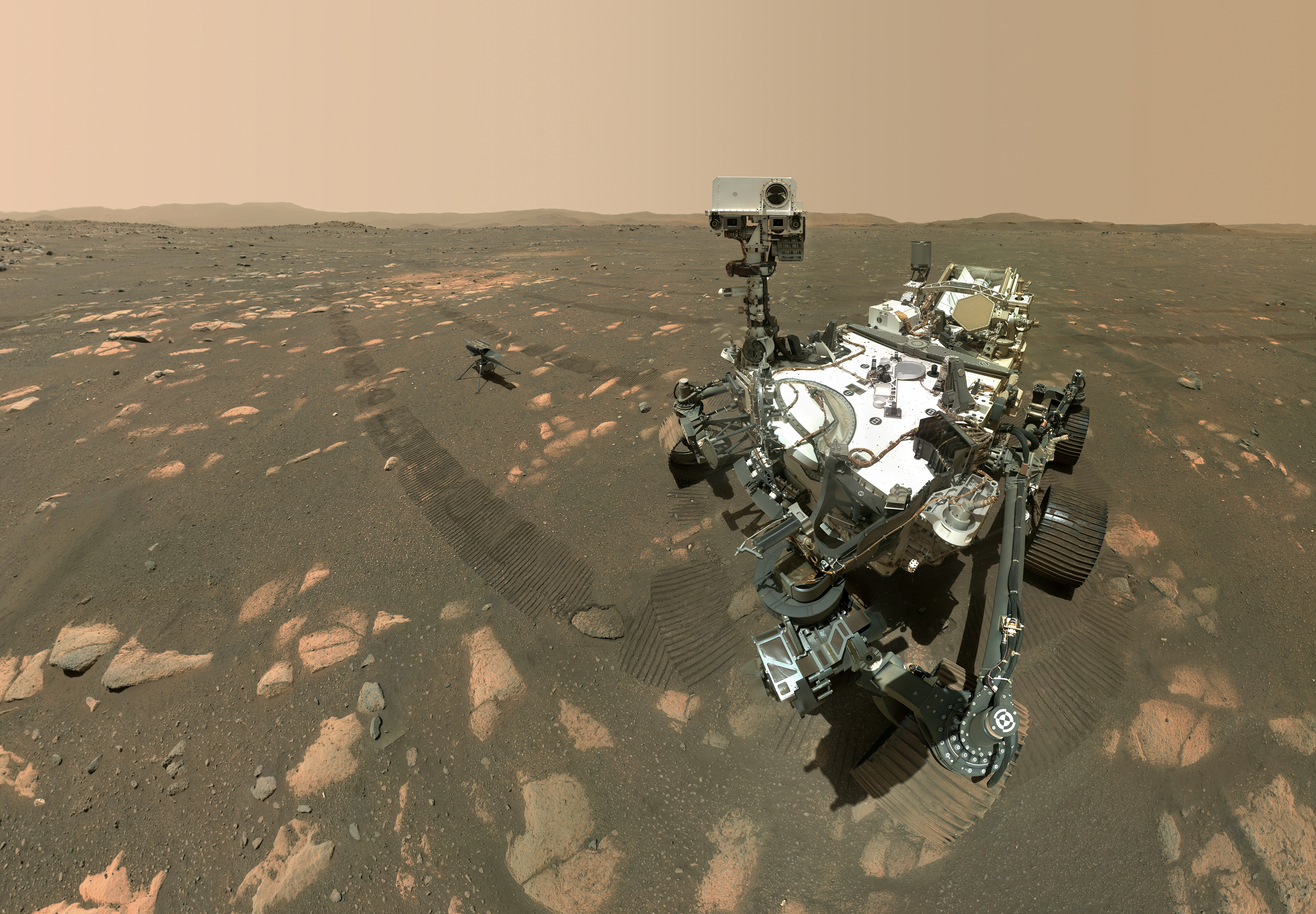

NASA robots Perseverance and Ingenuity on the surface of Mars, 2021

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

A bath bomb in my local chemist gave me pause for thought. It was formed into the shape of a smiley alien’s head; a classic Grey (although green) with a NASA logo stickered squarely between its eyes. I found it funny. NASA builds rockets and bath bombs – both are quite ‘science-y’, the position of the logo suggested the bath bomb had been used for target practice, or maybe the alien been playing with some kind of ‘which [space agency] are you?’ social media filter. The humour was short-lived; the current rhetoric surrounding real human aliens is appalling. The image of a lovable, goofy alien is often aimed at younger audiences; from there the message gets progressively darker and susceptible to propaganda about the other. A similar pattern can be seen around robots and more recently, artificial intelligence. Learning to look closely at what we assign human characteristics and behaviours to can provide compelling insights into how humans think and understand the world. Even more telling, and especially on a topic that could be seen as too broad or too specialist for people to embrace easily, it can highlight what theoretical footholds we’ve been offered and by whom.

Over the spring of 2021, I spent some downtime following NASA’s Perseverance Mars Rovers’ fascinating Twitter (X) feed (@NASAPersevere)1 while it tracked the rover’s tense landing and gradual unfurling on Mars. The feed is still regularly updated—Perseverance, Percy to its friends, is persevering through a long to-do list of data collection. Written in the first person and at one time featuring the exploits of the rover’s tiny air-borne sidekick, Ingenuity, the account presents a loveable hero for NASA’s aims: a light, accessible way of engaging with a mind-bogglingly complex and expensive (publicly funded) program.

Like the smiley alien bath bomb, however, there is an uneasiness here, though in this instance from the contrast between the technological sophistication of the Perseverance rover and the perky simplistic nature of its public profile. Engaging anthropomorphism feels like a useful cover for any wider picture of human presence in space today. Only some see Mars as an unexplored, unknown territory. The cosmos has played a key role in many traditions and knowledge systems for centuries, and NASA mapping and data gathering is just one type of knowledge formation. With light pollution and Starlink satellites now hindering the ability to fully observe the night sky from many places on Earth2, there’s unquestionably more than one bigger picture to see, and we’re being shown the scientific equivalent of a cartoon as a data feed.

Well, calling it a cartoon might be a bit dramatic. It isn’t that bad. NASA does make most of its research publicly available so I could broaden the scope of my interest. I’m just too easily distracted by clever bits of technology being nice to each other. However, anthropologist Debbora Battaglia might refer to this sense of something missing or unease as the product of warp sampling—a moment in time repeated into the future without considering the possibly different set of social and cultural conditions in which it will be happening.3 The well-meaning-explorers-in-space narrative serves us a basic overview of events. However, we’ve watched similar stories play out through history, and the brutal extractivism of earth-side colonialism now makes us question our part in any exploration into the ‘unknown’. Battaglia suggests that the public, indeed humanity, could benefit from our current understanding of ourselves being translated, rather than simply transferred, into a new place and time. Our understanding of space is shifting so rapidly that old tools and tricks of translation are doomed to fail. So then, how should we do it?

Seeing like a rover

Battaglia is among a growing number of social scientists who acknowledge the importance of exploring the various human understandings of other-worldly atmospheres. Stefan Helmreich, for example, observes the work of marine macrobiologists in the 2009 book Alien Ocean4. Discovering microbes that can survive in circumstances inhospitable to humans has helped us question the limits of what we consider ‘life’ and reevaluate whatever belief we hold of nature and its boundaries. Add to this increasingly sophisticated ‘artificial’ nature, and the boundaries are blurred even further.5 6

In an article from 2012, entitled Seeing Like the Mars Curiosity Rover,7 Brigette Nerlich uses Janet Vertesis’s 2003 study8 of engineers working on NASA’s Spirit and Opportunity rovers to explore some possible benefits of these blurred boundaries. The engineers working with the rovers over several years described how they had ‘learned to see like a rover’. Nerlich summarises, ‘They developed an embodied relationship with their distant robots which both anthropomorphised the robots and technomorphised the team’.

Vertesis’s study described the anthropomorphism the engineers engaged with to allow for a more immediate shared understanding of the functions of Spirit and Opportunity; discussing ‘what’s under our feet’ in reference to the ground beneath the rovers, the cameras that ‘stare’ or ‘look’ at the landscape and material around them. But it’s the concept of technomorphism, being immersed in the situation enough to innately interpret the way the technology understands a situation, that holds the most interesting advantage. For example, the rovers could not see the world in colour but could read parts of the spectrum that humans couldn’t. The researchers learned to translate this using visualization technologies and now ‘see’ and accept this new information. Our grasp of the range of possibilities in our nature is crucially extended by becoming familiar to another. Vertesis’s study described the anthropomorphism the engineers engaged in, including the phrase ‘what’s under our feet’ in reference to the ground beneath the rovers, the cameras that ‘stare’ or ‘look’ at the landscape and material around them, all terms which enabled a more immediate shared understanding of the functions of Spirit and Opportunity. But it’s the concept of technomorphism, being immersed in the situation enough to innately interpret the way the technology understands a situation, that holds the most interesting advantage. For example, the rovers could not see the world in colour but could read parts of the spectrum that humans couldn’t. The researchers learned to translate this using visualization technologies and now ‘see’ and accept this new information. We crucially extend our grasp of the range of possibilities in our nature by becoming familiar to another.

The artist James Bridle sums this up in their opening talk for the exhibition Through Other Eyes,9 ‘Technologies that we are developing at present, artificial intelligence being a key example, might not actually be a tool unto itself that we’re mostly misusing, but a tool that we could use to understand the natural world of which we are very much a part, in entirely new ways’. Bridle describes, as an example, the Wood Wide Web—the subterranean system of roots and fungal structures which aids a forest’s survival by linking plants for nutrient exchange and communication. It was named the Wood Wide Web because some of the researchers who discovered the existence of the system had been part of the research group given access to the early internet in the 1980s—and have noted that they only recognized that this was a network because they knew what a computer network looked like.

To the reflection and beyond

So if we have the opportunity to immerse ourselves enough in unfamiliar ways of seeing (without being too corrupted by bath bombs and cheery cowboy space-machines), humans are actually more than capable of translating and adapting to progress. A view Lucy Suchman explores and celebrates in her 2006 book Human-Machine Reconfigurations.10 Suchman argues that by transferring our existing ways of seeing onto new developments, we restrict our understanding of space, robots, artificial intelligence, and so on, to merely a reflection of our own inadequacies on Earth.

Computer systems are unique amongst other tools used by humans in that they are irreducibly complex. Like the materiality of space, the actual workings of a complex computer system exist for most of us in our imaginations, making them vulnerable to our biases and perspectives. However, according to Suchman, this isn’t a reason to cancel the relationship; it could be a way to get the most out of it. If we acknowledge these biases and perspectives for what they are and approach them critically, humans can learn to understand ourselves, as well as the computer systems more deeply. In his essay, Extraterrestrial Relativism11, Helmreich points out the word extreme itself begs the question: to whom or what, and in Anatomy of AI,12 Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler expose not a sentient computer system trying to take over the world, but very human, ruthlessly exploitative power structures hiding within the Trojan horse of a seemingly mundane home entertainment system.

Despite persuasive attempts to direct how we use AI, when we encounter it, we each move beyond the hype and develop our own unique ways of working or playing or just existing with these new tools. Once technology is made even a bit accessible, and we start learning its ways for ourselves, we open ourselves up to new readings of the world through this different translation, and to limitless future possibilities. Those with extractivist tendencies may be motivated to drive technological progress, but they seldom control the whole story. Sometimes, just when hope seems lost, humans tend to show that things are not so easy to predict.

To return to my enjoyment of the Perseverance / Ingenuity Twitter (X) feed, I was curious to know how an early celebratory selfie of the robots together on Mars had been taken, as I was under the impression that Perseverance’s’ ‘face’ was the only obvious camera. The website Mars.nasa.gov13 had the answer. The selfie had been taken on a second camera, the Watson camera, specifically meant for taking detailed short-range images on an extendable arm. As the camera isn’t capable of taking the wide view necessary to fit both robots in one image, the selfie is a series of 62 raw image captures, each from a slightly different angle, then sent back to earth to be stitched together. There is even an animated version in which Perseverance turns to look over at Ingenuity in one extra, slightly useless, head position. Was there a good data-capturing reason behind this, or was it just publicity-savvy? The selfies are costly, both in resources available to the rover and the human/machine labour involved in compiling them earthside. Still, perhaps this bond with the characters is essential to engage us. Indeed, the selfie was recently posted again on @NASAPersevere as an emotional nod to the end of the duo when the Ingenuity helicopter mission ended abruptly. However, no matter how useful they are, the process involved in creating the rover selfies – the way the different angles are overlaid in the final images – means that any trace of the camera is obscured from the viewer. It’s hard to see how they were taken, we can’t absorb the workings of the technology. One narrative is so foregrounded that the translation is hard to make out.

An article published on aeon.co by the science writer Philip Ball entitled Why our Imagination for Alien Life is so Impoverished14 had attracted twenty-six public comments at the time of writing. Some are humorous, others expand on the article, one has been removed, but my favourite comment simply quotes a poem:

“Only if you don’t know what flowers,

stones, and rivers are

Can you talk about their feelings.

To talk about the soul of flowers, stones, and rivers,

Is to talk about yourself, about your delusions.

Thank God stones are just stones,

And rivers just rivers,

And flowers just flowers.”

— Extract from Fernando Pessoa’s poem:

Today I Read Nearly Two Pages

References

- https://twitter.com/NASAPersevere ↩︎

- https://www.newscientist.com/article/2229643-spacex-starlink-satellites-could-be-existential-threat-to-astronomy/ ↩︎

- Battaglia, Debbora “Life as We Don’t Yet Know It,” in Imagining Outer Space, ed. Alexander C.T. Geppert (European Architecture, vol.1, 2018) p.232

https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/25970/Geppert%202012%20-%20Imagining%20Outer%20Space.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#%5B%7B%22num%22%3A738%2C%22gen%22%3A0%7D%2C%7B%22name%22%3A%22Fit%22%7D%5D ↩︎ - Helmreich, Stefan “Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in Microbial Seas” University of California Press: Berkeley, 2012. ↩︎

- Helmreich, Stefan “Silicon Second Nature: Culturing Artificial Life in a Digital World” University of California Press: Berkeley, CA 1998 ↩︎

- https://cajundiscordian.medium.com/is-lamda-sentient-an-interview-ea64d916d917 ↩︎

- Nerlich, Brigitte Seeing Like the Mars Curiosity Rover https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/makingsciencepublic/2012/08/08/seeing-like-the-mars-curiosity-rover/ ↩︎

- Vertesi, Janet “Seeing like a Rover: Visualization, embodiment, and interaction on the Mars Exploration Rover Mission”

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/0306312712444645 ↩︎ - James Bridle speaking at the launch of Through Other Eyes exhibition at NeMe Arts Centre, Cyprus: https://www.neme.org/projects/through-other-eyes ↩︎

- Suchman, Lucy “Human-Machine Reconfigurations; Plans and Situated Actions, Cambridge University Press, 2006 https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/humanmachine-reconfigurations/9D53E602BA9BB5209271460F92D00EFE ↩︎

- Helmreich, Stefan “Extraterrestrial Relativism” in Anthropological Quarterly, Vol.85, No.4

http://anthropology.mit.edu/sites/default/files/documents/helmreich_extraterrestrial_relativism.pdf ↩︎ - https://anatomyof.ai/ ↩︎

- Perseverance’s Selfie with Ingenuity https://mars.nasa.gov/resources/25790/perseverances-selfie-with-ingenuity/ ↩︎

- Ball, Philip “Why our Imagination for Alien Life is so Impoverished”

https://aeon.co/ideas/why-our-imagination-for-alien-life-is-so-impoverished ↩︎

About Kate Rogers

Kate Rogers is a London-based graphic designer and researcher with a multidisciplinary approach. She holds a BA in visual communication from Portsmouth University and a MSc in digital anthropology from UCL. At the moment she spends alot of time talking to people about how they use technology in their design practise. She likes eavesdropping on buses.